The definition, vision and perception of stewardship can be variable. How do we bring these stewardship definitions together – what does this look like?

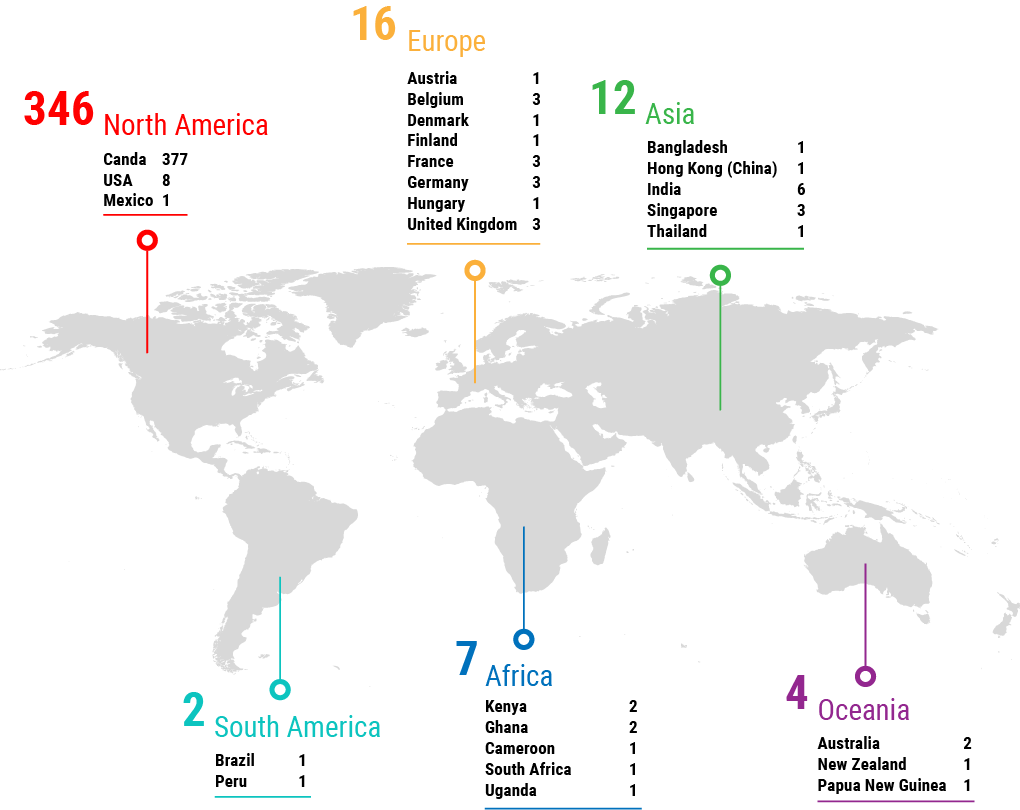

Many people have perceived needs and have articulated them in remarkably similar ways. There is a great common understanding. A big concept in stewardship is sustainability, where the value of antimicrobials is important. The infrastructure required to thoughtfully design a collaborative stewardship network is possible. Being able to bring these activities together across the different domains of human health, public health, veterinary public health, veterinary medicine, animal agriculture and environmental health is critical. We need to use out-of-the box thinking and engage with non-traditional stakeholders, starting at a grassroots level, trying to move away from recommendations and move to more of a sense of engagement and support. This applies to both the public and private sectors. In order for interventions to be feasible long-term, we need to understand that different groups already know their needs well and have ideas on how to approach those needs. When speaking of stewardship, there has been a change from a top-down to bottom-up approach, but in the animal health regulatory field this is still being directed in black and white ways through policing antimicrobial use and resistance rather than bringing together stakeholders to have important conversations to develop something feasible at the global level. Regulations need to be feasible for compliance, and government agencies need to work together.

PHAC is funding a group to develop an AMR Network. Does Canada’s Federal-Provincial/Territorial (FPT) structure require political buy-in or political distance to make this successful? In Alberta, the political will is for made-in-Alberta solutions, for example. How do we deal with potential political division?

Some of what we have now is working because it is separate from politics. In CIPARS, there is academic collaboration that forms a de-facto network that skips the FPT level, but skipping that level weakens the structure. We have not tried to tackle that head on, but during this global COVID-19 public health challenge could be the time to take it into a political arena. We have to have a cohesive response. The message does not seem to get through politically, no matter how many different approaches we take. The made-in-Alberta suggestion begs the question of “do you understand the scope of the problem?”

Is Canada ready to set targets for reductions in volume of antimicrobial use? Global solutions are required, but we act at national levels and must also act within our FPT structure in Canada.

The concept of thresholds is most relevant where robust data are available to inform what a reasonable amount of use is, or examples from elsewhere where decreasing AMU has not had significant negative impacts. People can respond to a target — it is a palpable thing, so it depends on the scenario. Stewardship should not just be about the drugs and/or tools, it needs to be about the population in question, and the microbes as well.

Stewardship is not a quick fix, but quick wins that individuals can identify within their own context are important. How can we pursue this? It feels like an imperative in a rapidly changing and dynamic environment that is distracted by so many other factors.

It took the global pandemic for governments to realize that vaccine confidence and hesitancy are a big deal and this one-size approach of telling people to take the vaccine did not fit. We have to realize that everybody has different reasons for hesitancy. This is a complex issue but in order to build trust for people to buy in, we definitely need the government/political buy-in. However, on the ground you need people with common ground to build trust — those are the local champions within the various fields. Implementation science, or process-based approaches where you are able to set metrics for your progress toward a goal, are really useful from the high-level perspective. Relating to the people who do not think that AMR and AMS mean anything to them, personally or professionally, is critically important. It is hard for government when this is not one particular organization from the industry side to communicate to the general producer or general public.

Who should be educating the public on the critical impact of AMR and stewardship, and where is the opportunity for public education campaigns like “Do Bugs Need Drugs”? How important is it to get the general public involved in understanding stewardship and what’s the best way to do it?

People are increasingly and incredibly engaged in public health and biomedical research over the last year. Although this interest was born out of desperation and necessity, it has become normal to have scientists, epidemiologists and doctors talking about high-end scientific concepts on a regular basis. Is there a way we can leverage this level of public engagement? When all of the communication around the pandemic finally ends, there will be a void during which there will still be an activated public and that provides an opportunity to work with them. The public is somewhat used to being lectured about not taking antimicrobials, so we have to make sure the message remains fresh and more sophisticated because it is a more sophisticated group now. We need public outreach but maybe we need to move away from decision making and have the sustainable approach be the default. An example is removing triclosan from soap. There is varied knowledge across groups so there is a certain requirement of education. In addition to public engagement, there is a need for discussion at the point of care when consideration of use of an antimicrobial is happening. The prescriber needs to be primed to discuss this with members of the public as well. A lot of people know about AMR or stewardship in some form, but there is a worry that things will only happen if there is a regulatory requirement that needs to be met.

How do you actually evaluate the impacts of a specific intervention when you have got these things happening at the same time or with complicated measurements?

If you are going to have an intervention, you should have something you can follow and measure. If you do a targeted intervention that involves audit and feedback in a particular domain, you can follow that. When we look at the large-scale desires of stewardship in terms of overall antimicrobial use, small changes in a lot of different areas might make a larger collective difference in terms of antimicrobial exposure that is clinically meaningful. You have to make sure the metric makes sense for what you are looking at.

Do we need Canadian manufacturing to support vaccines and other interventions for a real made-in-Canada solution? In a world where cradle-to-grave interests are growing, what is the increasing responsibility of product stewardship by manufacturers regarding product lifecycle?

We do not even have that for plastics and other macro scale waste, much less things that are very difficult to see, such as antimicrobials. If we had that kind of approach, what would it take to incentivize industry to be able to build those costs in and to follow products all the way through to disposal? Not just antimicrobial return programs. How do we handle, for example, excretion of antimicrobials by animals into the environment? In Canada we have recovery of unused medicines but it is hard to know how efficient that is. When a product is sold, you have no idea how much actually goes into an animal and where unused product ends up.

Dr. Constantinescu talked about a hierarchy of experience being an impediment to prudent decision making and use. How might a managed network approach consider this?

A managed network requires a feedback loop so that quality assurance is monitored and unintended consequences can be identified. You have to pass on control in terms of evaluation and implementation in order to remove hierarchy.

Where does maternal-fetal health fit into the stewardship spectrum and does antimicrobial use during pregnancy affect resistance in the mother and the baby and are there any gains there we should be thinking of?

There are a lot of unknowns, lack of data, etc. We have our short list of safe drugs and we try to use medications very responsibly in pregnancy to minimize exposure because of those unknowns. Part of the issue is we do not really know who “owns” this area. We know that if moms are on antimicrobials during pregnancy, we do see higher rates of resistance in babies when they come in with invasive infections. There are huge implications to the microbiome — how huge, we do not know. Pregnant women are notoriously not included in studies and this may be why recommendations take so long to change in this field.

Realizing that there are some differences between WHO, OIE and Health Canada’s antimicrobial categorization, how can we build on or apply stewardship groups for human health in the Canadian context?

The concept of the groupings came forward from trying to de-emphasize certain antimicrobials from widespread use in animal health because of their potential impacts of resistance in human health. There has been a default categorization that is starting to evolve when we think about the stewardship of specific antimicrobials in human health (i.e., fluoroquinolones are now the bad guys and trying to de-emphasize them in first-line therapy). So, there is some categorization but we are limited because in human health we are always reacting with both empirical and targeted therapy. Antimicrobial studies should include more ecologic data on the incidence of resistance that happens when you use that antimicrobial in terms of that person’s flora.

Can the stewardship of antimicrobials be tied to changes in animal stewardship or husbandry? Is the public willing to pay the resulting cost for reduction in antimicrobial use for some of these stewardship changes?

We are seeing food price increases related to animal feed and a variety of other things. If we do get carbon taxes incorporated properly into food prices, then consumers will recognize this cost.

Use the term antimicrobial footprint as carbon footprint is used. Everyone using/giving antimicrobials leaves a footprint.

Again, this is a global problem because we export a lot of food to countries that are protein or other deficient and we do not want to exacerbate food security problems in low-income countries by raising the cost of food or reducing production due to animal disease. At the same time, we have to recognize that we cannot continue to create externalities from our food production system. They have to be costed properly. In some countries, the connection between antimicrobial use and animal welfare/husbandry has not been communicated well.